From the outside, there has been a series of uninterrupted revolutions in the art world over the past few years.

Since they found widespread notoriety early last year, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have commanded tens of millions of dollars in price tags for digital works of art. But critics have described them as rubbish of no value at all, meaningless to art patrons, and the artists themselves have complained about the theft of their work, “casting” without their knowledge.

Meanwhile, the web3-based metaverse is being touted as the new home for this art — a digital environment Facebook has invested billions of dollars in, even if its own employees aren’t adopting it.

More recently, AI art (which can create art based on text prompts or simple unfinished sketches) has been promoted as a way to “democratize” art, allowing those without the technical skills to create their own illustrations cheaply and quickly—although only in these The system has been trained on billions of existing examples of art, often without the consent or payment of the original creators.

So what was given? Why has the art world been hit again and again over the past year with changes advertised as benefiting artists but seemingly upending how art is made and consumed? Why do innovations in the tech world that are supposed to affect the way society as a whole work seem to explode and spark controversy, especially in the arts?

See how blockchain can be developed to verify Aboriginal art and use it in healthcare.

“These technologies are showing themselves, looking for ways to get the art world talking,” explained Rob Horning, a technology writer and founding editor of Real Life magazine, noting the rise of NFTs in particular.

An NFT is a creation that runs primarily from the Ethereum blockchain — effectively a system for publicly recording and tracking online transactions. The main purpose of the system is to enable the Ethereum cryptocurrency (using “fungible” (exchangeable) tokens, meaning they can be traded with each other as functionally identical items).

By contrast, the “irreplaceable” nature of an NFT means that it is unique – no two are interchangeable. This means they can be linked to digital artworks (which themselves are rarely stored on the blockchain) to give them authenticity.

Essentially, this means that the valuable part of NFTs in the visual arts world is the perception of value. While the digital art to which it is associated can be copied an unlimited number of times, only one person can say they own the “authentic” copy.

Horning said the technology had little clear purpose until it created a marketplace for itself to sell digital art.

Step Back, Criticism of Art World Technology

While the initially stated goal was to enable unrepresented artists to sell their work, NFTs have proven to be more divided among artists.

although theft and Piracy Having proven to be a huge problem in the space, opposition to NFTs has become evident from the very group they were supposed to help in the first place: smaller artists who, instead of finding new avenues to sell their work, find themselves mingled with technology and cryptocurrencies Subcultures use and sell their work without the artist’s consent.

But Horning said that despite the resistance, the technology continues to roll out and roll out, as NFTs and cryptocurrencies remain “as important as the buzz surrounding them.”

“People who invest in cryptocurrencies have been under pressure to get cryptocurrencies in the news, to get people talking about cryptocurrencies,” he said. “One of the ways you can do that is to get artists to talk about crypto, or have artists make things that are related to crypto or crypto. NFT related stuff.”

The bumpy intersection of the art and tech worlds is now colliding with the art of artificial intelligence, though not unfamiliar. With machine learning models like DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, and Midjourney, anyone with an internet connection can enter a few prompts and generate any image they want.

As with NFTs, some artists have fought back. Artists like Simon Stålenhag – their sci-fi scenes inspired the Amazon Prime collection cycle story — and web cartoonist Sarah Andersen Complained that the systems were trained on publicly available art, including their own work. This enables users to request images be generated in the style of living artists, mimicking their work — and potentially taking business away from them.

The AI art generator “is not in the hands of the artist right now. It’s in the hands of the early adopters of technology,” Stålenhag told Business Insider in a recent interview.

Blair Attard-Frost is a PhD student at the University of Toronto who studies the impact of AI and ethical ways of implementing AI in industry. The artists, they said, belonged to the “labor displaced” camp, whose work was used to create and implement artificial intelligence with little or no play.

But these problems arise in many industries implementing AI. The reason it’s more visible in the art world is because of the centrality of art to people’s everyday lives.

“One of the reasons this ‘AI artist’ thing is getting so much attention is because it’s more common, right?” Attard-Frost said. “It affects everyone, it unlocks all kinds of new capabilities for a lot of people … in a way those more specialized apps don’t do that.”

There are a number of reasons why these technological inventions have forged such strong ties with the art world and not elsewhere. That’s partly due to the industry’s shift toward focusing on the sale of art rather than its creation, said Robert Enright, senior contributing editor at Border Crossing Magazine in Manitoba and professor of art theory and critical studies at the University of Guelph. “

“One thing that has happened — I think that explains why NFTs and why there is this search for new things to sell — I think in many ways, art marketing has become a very, very important part of this process,” Enright said.

“Because there is so much money in the world right now, and because the rich have to find something to do with their money, one of the things they do is pay dearly for art.”

At the same time, as Attard-Frost explains, sooner or later these technologies will appear in all areas of life. They are only taking the first steps in the art world, and regulation around many of these technologies is still in its infancy, and they compare it to the “Wild West.”

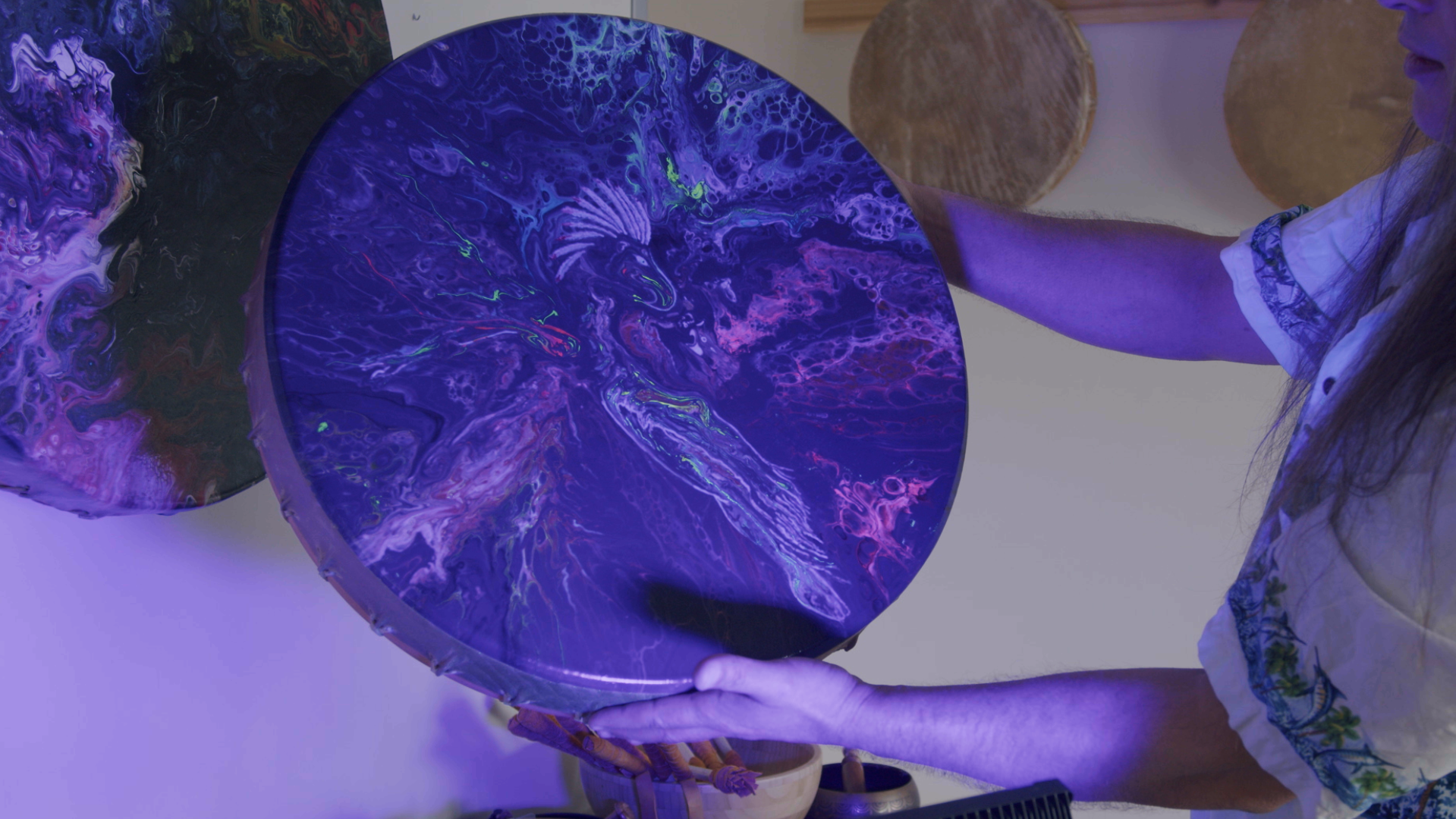

But American artist Sara Ludy’s work often makes use of new technology, which she says is just emblematic of the field. The nature of art is experimental, and it always draws artists to new mediums and techniques that are not yet widely understood.

While this can make it difficult for artists to keep up with the changing demands of the tools they need to master — and lead to potentially predatory commercial practices that see opportunity for those outside the art world — art and technology will always find themselves intertwined, she said. Say.

“Artists are driven to expand our definition of the world and of self. Technology is here to expand our definition of self and connection and all of those things,” Ludy said. “So … our motivations are very similar.”